Back to the Future—

New York's Lost Transit Legacy

Page 4

The Great Depression

In 1929, the Great

Depression set in. This largest of American business panics was a great

blow to the electric railway industry in New York and nationally and one

of the key factors in the industry’s decline.

The Depression gave a boost to the City’s desire to own and operate not

only its under-construction Independent system, but the BMT and IRT as

well.

The economic downturn was the last straw

for the IRT: the decline in ridership was added to the financial strains

of its onerous lease of the Manhattan Elevated lines and the City’s

refusal to allow it to raise the five-cent fare. Bankruptcy was the IRT’s

lot, and selling out to the City began to look more like salvation than

defeat.

Innovation in Hard

Times

The BMT refused to go down for the

count, however. Management felt it could overcome both hard times and City

competition with innovation. As it had in the past, it went direct to the

public to show it the future at a time when most were grateful to live

day-to-day.

In December 1932, discussions

began as to the construction of an aluminum rapid transit car. In June

1933, the Transit Commission gave its approval for the BMT to construct

such a car. A few months later, it approved a stainless steel car as

well.

On June 19th and 20th, 1934, the

aluminum car, unofficially styled The Green Hornet, made its public debut at the

Park Row terminal of the BMT elevated lines. Built by the Pullman Car and

Manufacturing Corporation, it featured a futuristic curved body design

which earned it the nickname “Blimp,” but this was in jest, as this

two-toned green beauty heralded a new era for transit

riders.

Later in 1934 the pioneer of stainless

steel railway construction, the J.G. Budd Company, delivered its own

version of the elevated car of the future, popularly called the “Zephyr”

after the ultra-modern diesel units Budd was building for the Burlington

railroad lines.

Both cars were dubbed “Multi-Section Cars” by the

BMT. The cars appeared to solve all the BMT’s future elevated car needs at

once. The Hornet, Zephyr and the 1935 production order of

25 multi-section cars each consisted of five sections combined into a single

unit and carried on six trucks. This was done using the principle of articulation, of which the BMT was a leading

advocate.

Articulated cars had a truck

assembly (the mechanism holding the running wheels) at the extreme ends of

each five-section unit, plus a single truck underneath the joints between

any two sections.

The term “articulated” is used in nature to describe snakes,

whose segmented bodies allow them to slither through tight spots that would

trap larger, bulkier, beasts. The snake analogy aptly describes one of the

great advantages of the Multi-Section Cars—they snaked around the tight curves

of the older parts of Brooklyn’s elevated system. Paradoxically, they created a

longer car for the passenger. The Hornet was 170 feet overall, as long as

the body sections of four elevated cars, yet riders could stroll among the five

individual sections through passageways called vestibules,

without subjecting themselves to the discomforts of weather or the danger

of passing between swaying cars.

The Multi-Section cars were also

fast. Lighter weight and more powerful motors made riding them a

hold-your-hat experience, even if you weren’t wearing one. The BMT estimated

that a fleet of Hornets would

trim the running time of a Fulton Street Local, encompassing 11.3 miles

and 32 station stops, from 49 to 36 minutes.

But what about weight? Could the BMT “lower the river” with cars capable

of operating on existing structures instead of “raising the bridge” with

the massive capital expenditures of completely rebuilding els or new

subway lines?

Although elevated cars were lighter in terms of axle loading

than subway cars, the weight per passenger carried, which determines how much

energy is used to carry each passenger, is comparable. The BMT’s heaviest car,

the subway Triplex, weighed 212 pounds per square foot of floor area fully

loaded. A BRT el car worked out to a surprisingly close 204 pounds. The Green Hornet

slashed this weight to 158 pounds.

It is axle loading, however—the weight carried by each car

axle—that determines whether a car could operate on one of the old structures

at all. A loaded Triplex maxed out at 40,000 pounds per axle. A wooden elevated

car put 28,000 pounds on each axle, while the Hornet blew both away at

only 23,600 pounds.

In the early Fall of 1936,

after extensive revenue testing on the Canarsie Line, the BMT and its

passengers saw the first (and last) fruits of its light-weight technology

efforts. Multi-section cars, based on the Hornet design, began service

from the 14th Street subway in Manhattan to the outer reaches of the

Fulton Street elevated line.

Continued on page 5

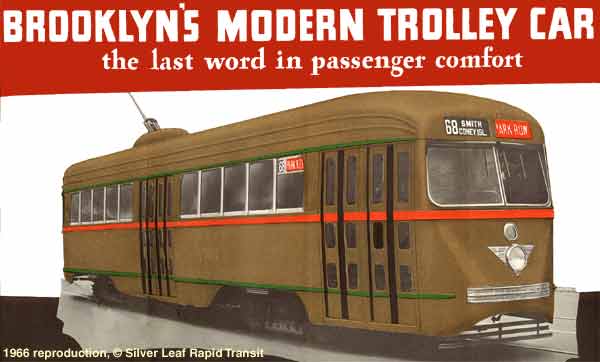

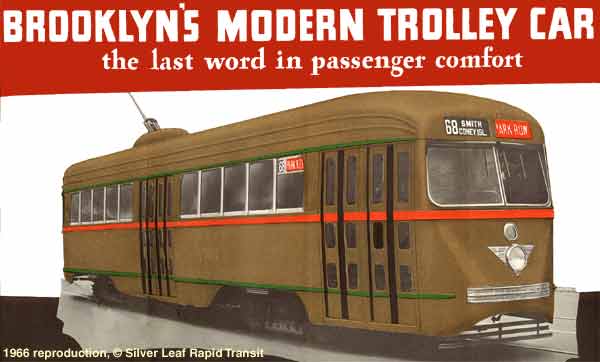

The BMT was also in

the forefront of advanced streetcar design, as announced by this 1936

brochure. Cars like this one spread across the U.S. and Canada and similar

designs were deployed worldwide. New York's Mayor LaGuardia forced the BMT

to cancel its order for an additional order of 500 of these cars.

Technology prioneered in this design was used in the

Bluebird. Paul Matus Collection

The Third Rail and The Third Rail

logo are trademarks of The Composing Stack Inc.

|