Page 11

Similarly, real estate interests harped on the need for metal as a reason for rapid demolition. Real Estate broker Harry Helmsley argued in February, 1942, that the el, an "eyesore, which long ago ceased to have an indispensable value, is going to be torn down eventually anyway. Under ordinary circumstances there might not be any hurry about it, but with the urgent need for metal the job should be done immediately." While Helmsley's comments on wartime priorities may have been valid, the Times reported his arguments in the Real Estate section. Removal of the el was still an issue of great interest to real estate interests. The politicians and brokers were up to their same old tricks, with the war as additional ammunition in their attack against the el.

Frank S. Williams, a representative from the War Production Board, wrote to Mayor La Guardia on April 6, 1942, saying that "because of the tremendous and immediate national need for maximum production, the urgent necessity of a continuous high rate of flow of all kinds of usable scrap to our steel mills is of the utmost importance." He went on to say that he hoped for "acquisition of the scrap materials in the present Second Avenue el ... as soon as possible." Clearly, there was a genuine need for scrap material, and if the Second Avenue el were to be demolished, it seemed that the resulting scrap would be put to good use. On April 21, Frank Williams appeared before the New York State Assembly. In the wake of his testimony, Queens Assemblymen softened their opposition to a bill that would authorize the demolition of the el. The New York Times hailed the event as a victory for the American war effort, writing that "the Queens members seemed ready to acknowledge that the needs of the whole country stood ahead of the needs of Queens for transportation service." The reality was not so clear-cut, however.

Far from serving "the needs of the whole country," those pressing for the el's demolition continued to do so for reasons of local interest. They merely took advantage of the War Production Board's need for scrap, and used it to create an added impetus for rapid demolition.

Even before Williams' April 6 letter, foes of the el were using the wartime need for scrap as an argument for removing the structure. The Times reported in February the arguments of City Councilman Stanley Issacs in favor of removing the el. Issacs argued that "scrap iron to be derived from [the el's] demolition ... has become increasingly valuable for war purposes." He also argued, however, that "the line now in operation costs the city about fifteen cents for every nickel fare collected." Issacs may genuinely have wanted to help the war effort, but there is no question that as a Councilman, he had a vested interest in improving the city's finances.

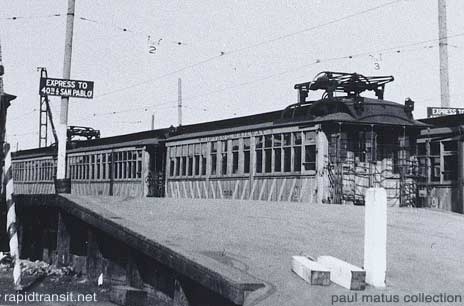

WAR DUTY. While LaGuardia and New York City officials were sanguine about the importance of rapid transit service for Queens residents, surplus equipment from the Manhattan els saw service carrying wartime workers on the Key System's Shipyard Railway in Oakland, CA.

Updated

©2001 Alexander Nobler Cohen. ©2001 The Composing Stack Inc. All rights reserved